Peculiarities of Basque Sheep Raising

In the beginning of October, I took part in an educational trip to the Basque Country (in both France and Spain), organized by the Estonian Association of Sheep and Goat Breeders.

I raise sheep as a hobby, so in the Basque country I saw a magnitude more of sheep (and mountains!) than what I see every day. The focus of the trip was on dairy sheep raising, but for me the aspect of their life which made me most envious, was the access to artificial insemination that is simple and works, too.

Sheep Cheese as a Commodity

The local sheep of the Latxa breed (they distinguish the types with white and dark heads) are very well adapted to the natural environment in the Basque region, and they produce an amount of milk that is both necessary and sufficient for the region. I found out that large amounts of cheese are eaten in the Basque country and not much is left over for export. The locals didn’t seem much interested in export, either. The focus is on keeping the local mountain farming way of life alive, and on carrying on the heritage. Sheep milk cheese is so common and eaten in such large amounts that one farm that we visited, has started producing goat milk cheese to be better seen on the market.

Keeping the heritage is more important to the Basque people than productivity, so that a foreign breed whose name I forgot, but who produce 3 times more milk than the local Latxa breed, are not allowed to be used for the traditional cheese.

The Latxa sheep with white heads look like this:

And here is an assortment of ones with dark heads:

It must be noted that when defining a breed, the nuances of the looks of the sheep is not the most important aspect, so there are quite different-looking types among the ones with dark heads:

There Is No Use for the Wool

Often when someone hears I raise sheep, they ask about the wool – whether I make yarn myself. When I say it takes a lot of time and is a tedious job that provides no significant income, some people are surprised.

It turns out that the problems are similar in the Basque country. In the past, it has been an important material, but there is basically no demand for it now. To get rid of the wool, it is simply burnt in valleys between the mountains. Here we can see a pile of wool in a barn, which will perhaps be burnt as well:

Well, the local Basque sheep don’t really have very soft or fine wool, after all. It felt more like the hair of some long-haired dog when I scratched them (some specimens allowed me to do it):

Artificial Insemination

Last autumn when we looked for a suitable ram for our small flock, we investigated the possibilities of artificial insemination, as well. We had read from UK and US literature that artificial insemination exists for sheep but it is a difficult procedure (involving surgery and risk), and we didn’t seem to find anyone doing it in Estonia. At that time I totally missed the point that the whole story was about using frozen sperm.

The Basque sheep raisers have the luxury of using the fresh semen of selected breeding rams. We visited an insemination station where those special selected rams lived, and whose semen must arrive inside the ewes in 8 hours for fertilization to take place. And even in that case, only 50% of the ewes get pregnant.

Thinking about our flock, this possibility would have both positive and negative sides for us. On the one hand, we wouldn’t have to buy a ram for which we don’t have enough pasture space away from the ewes, and who would have to be killed or sold soon after mating. On the other hand, getting 50% of the ewes pregnant would mean that we would need to feed one group one way and the other group another way during the winter. Thanks to the great work of LLouis, all our ewes were pregnant last winter, and it was very easy to feed them, with everybody getting the same ration. So in summary, it’s nice to know what is available to others, but with a small flock and a small piece of land, it’s very difficult to raise sheep in more than one group.

Anyway, here are some rams of the breeding station, with all the perfect traits and stuff. Because they are used to being around people, they will approach you and look for treats, too.

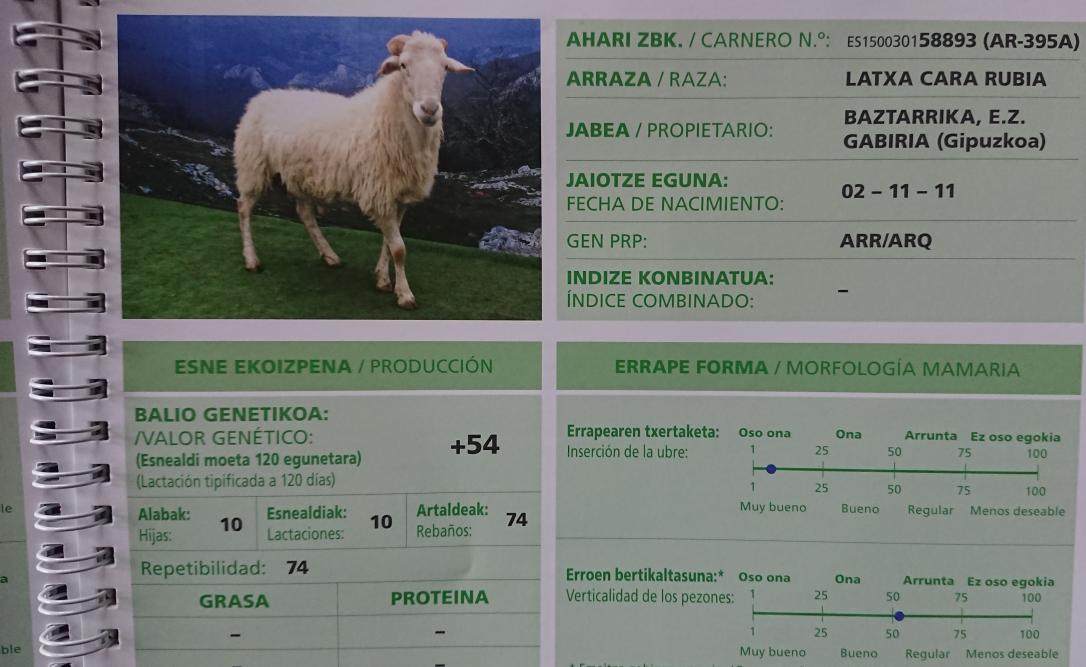

To add even more to the comprehensive breeding program, the organization that manages the breeding station, ARDIEKIN S.L., issues a catalog of rams each year. I don’t understand the text in the Basque language, but all the rams pose with mountains as the background, and have been nicely groomed.

The representatives of the organization said that the harvested sperm is available in the radius of a couple of hundred kilometers – this is close enough that in the 8 hours one is able to harvest the sperm, check it, transport and put it inside the ewes and still have some time buffer available. In Estonia, this kind of enviable infrastructure, considering the distances, might work in collaboration with Latvian sheep raisers, if we could find breeds that are officially bred and interesting in both countries. Maybe if the insemination station was located somewhere in the southern Estonia, there would be enough potential customers in the acceptable radius?

Stone Villages

The typical Basque village is very different from Estonian villages. While our houses are often a kilometer apart from each other (it depends on the type of village but this is the stereotype, anyway), the Basque villages have traditional houses side-by-side. The animals and fields are situated around the village and in the mountains. I was very much surprised by the fact that there is a certain minimal(!) size defined for the houses by the government (including the number of floors). The locals would like to have smaller houses but they’re not allowed to.

A typical village street looks like this:

… but the small town of Eulate reminded me of Toompea in the old town of Tallinn:

… and stone houses are often decorated with the symbol of the Basque Country, depicted here on the balconies:

As a conclusion, here is a photo of a backyard behind the stone houses, where I found a couple of sheep and a lamb. The Basque country is literally full of sheep, and the ones that are not in pastures or in barns, hide away at home in the backyard.